(You probably want to read parts one, two, three, four, five, six, seven and eight before starting this).

(You probably want to read parts one, two, three, four, five, six, seven and eight before starting this).

When designing a game, the most important aspect of your design is how the game ends.

This is a self-evident truth, but it is amazing how often it is overlooked. The game should have a simple goal, which drives the game play towards an inevitable conclusion. In Chess, you must attack your opponent's king and leave your opponent no safe move to escape. In Angband, your goal is three-fold:

1. Stay alive.

2. Kill Sauron.

3. Kill Morgoth.

Everything else in the game is extraneous.

Unangband complicates this, by putting further road blocks in the way. In this process, I've made the intermediate game-play arguably more enjoyable, but the final battle with Morgoth is anti-climatic as a result. And the final few levels: well... complaints have been made about the length of the game and unrelenting difficulty at the lowest depths.

Counterpoint: People don't play games to their conclusion. And when they do, many games break the rules for the final boss fight that they have established in the lead up to this encounter. I enjoy games the most which end up in a post-modern explosion, or a falling denouement, breaking the rules of the game to transcend its boundaries.

The fight with Morgoth should be game breaking - explosive, memorable, unusual. He should curse your weapons and armour, blasting your precious gains from your body, just as he summons the uniques you have previously killed from beyond the grave to fight you again.

Or the encounter should be compeletely unexpected: An Architect sitting in a room full of monitors, explaining consequence of choice and free thought, or Count Dooku telling Obi-Wan the Emporer's plans because Kenobi is blind to the truth when it comes from his enemy. You should have your weapons stripped from you, and fight to death with crysknives in front of the Shaddam IV, after all the trappings of a far future civilisation are stripped away. Having lost your armoury, you should face Combine soldiers with a super-charged version of the Zero Point energy device, manipulating your environment as a shield, weapon, key.

Angband's goal is often parodied:

1. Go to General Store

2. Buy lantern

3. Kill Morgoth

and this parody reveals as much about the game play as the surface incentives the player responds to.

So how should the game end?

The point I argued to start with suggests that the final fight should be an expression of the best the player can be. That suggests an opponent which encourages the player to excel at what they are good at, as opposed to negating their most powerful abilities. If the player uses fire, they'll need to conjure up more powerful fire than they've ever used before. If they use swords, they'll need to wield it for longer, cut deeper and let more blood flow than any other battle. Whatever abilities they have, they should be tested.

But the final fight with Morgoth does none of this.

There is a good candidate for this type of game design, who can shift shapes so that at any point in time they may be vulnerable or immune to the player's attacks, forcing the player to switch strategies and retreat when they are weak, and advance when they are strong. I am, of course, referring to the shape shifter Sauron. And it seems to me that a well thought out implementation similar to FAAngband's should allow the player to be the best that they can be, provided the timing is right and fortune favours them.

But it's not by accident that the first two movie examples I gave are from the second 'difficult' movie in the triology (And I deliberately avoided mentioning the unveiling of a filial relationship in a related trilogy). It is undoubtedly true in Angband and related roguelikes that you will have had a closer brush with death at some point during game play then you will in the final fight with Morgoth.

This is especially difficult in role playing games, where the accumulation and management of resources is a critical part of the game. Many RPGs can be played conservatively, and most have collectible resets, which allow you to recover during the final fight back to your starting condition. As a result, since it is the final fight, your hit points are equivalent to what you currently have, plus whatever healing resources that you have had the patience to collect during the game.

And this patience could equally be viewed as grind. If you can collect one 'potion of Life' (or Pheonix Down, or whatever your game equivalent is) for every twenty minutes of game play, most people will grind out this collection process until they have a huge buffer of life before the final fight, because they can. And I don't want to encourage grind.

What does Rogue do? Looking at the progenitor of all roguelikes is an important source of inspiration. Rogue ramps up the difficulty, the further you play, so that at the lowest levels of the dungeon, even surviving is a victory in itself. Other games, notably Steamband, make the final few levels a desperate succession of calculated gambles. I could do this for Unangband, because as anyone who knows Tolkein's mythology well, there are worse things out there than Morgoth.

I'm talking about Ungoliant.

Morgoth is no slouch in the ultimate evil department, but even he is afraid of Ungoliant. He needed a host of Balrog to help fight her off, after he refused to give her the Silmarils. If I make Ungoliant suitably dangerous, and have her wandering around the depths of Angband, the player may fear for their life long enough that the risk of looking for healing outweighs the risk of fighting Morgoth.

So two possible strategies to improve the Unangband end game are to allow Sauron to shape-shift, and to make Ungoliant a force to be reckoned with.

And how does dungeon design complement this?

I expect that the deepest levels of the dungeon will be the most open. This makes the player uncomfortable and in the riskiest position that they can be in. Open spaces force the player to creep around, a mouse-like Beren and Luthien avoiding the greatest dangers, but given enough free passage to pick their own path to their enemies. It'll let me give free reign to adopt the open levels that FAAngband has, while retaining the player focus on a central location where their ultimate enemy dwells - a great blackened throne holding Morgoth on the deepest level of the dungeon, or a great gate to the next level guarded by Sauron (or others), which must be passed.

I suspect, given the blasted nature of Morgoth's lair, that there'll be other undiscovered difficulties for the player to contend with. Zones where magic cannot be cast, items cannot be used, howling winds that knock arrows and thrown weapons out of the air. A miasma hanging over the whole level which drains health, experience and mana, so that the longer the player fights, the more resources they'll consume. The sunken graves of previous adventurers may find their roots here, so that the ghosts of player's past may stalk the level. More surprises yet.

I think I'll get there myself some day.

Tuesday, 22 April 2008

Unangband Dungeon Generation - Part Nine (Endgame)

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

20:38

5

comments

![]()

Labels: articles, procedural generation, unangband

Surfer Girl Reviews Star Wars

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

14:05

0

comments

![]()

Labels: game industry, links

Monday, 21 April 2008

Money where you mouth is

I've only just noticed this, but time has come around again for contributions towards angband.oook.cz's web forum software. I don't particularly care to argue the merits for and against web forum software, but I do support assisting one of the real assets to the Angband community: Pav.

Details on how to make your contribution here.

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

16:24

1 comments

![]()

Sunday, 20 April 2008

Unangband 0.6.2 gold has been released

This release is a development check point which allows you to play a "relatively" bug free version of Unangband, while we significantly hack on the source to add extra features that may potentially destabilize further releases.

For further details, check the Unangband home page.

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

21:25

0

comments

![]()

Thursday, 17 April 2008

Unangband Dungeon Generation - Part Eight (Persistence)

(You probably want to read parts one, two, three, four, five, six and seven before starting this).

It's been a while since I've updated this series of articles, particularly as I prematurely hinted I might be finishing the series in part eight. But I've been thinking a lot more about dungeon generation recently, and how this persistence is important, if you'll excuse the pun.

In most modern games, you take persistence for granted. You open a door, come back to the same location, and the door stays open - blow a hole in a wall, and the hole remains. But scratch the surface of many games and you'll see that persistence is a facade.

Persistence requires memory, a precious resource in computer science that for a long time was heavily restricted. It is only in the last few years that multi-gigabyte memory on a desktop PC is the norm. Streaming the environment to and from disk causes it's own issues, which is why fewer games than you'd expect take advantage of this. But keeping track of persistent object interactions also increases the overall complexity (think CPU utilisation) of the game space as well.

Grand Theft Auto's disappearing cars are a classic example of reclaiming a resource to reduce the scene complexity as well as work on an environment with limited memory. If you walk half a block from any car you've driven and come back it'll be gone. Even Doom 3 cheats death, with the bodies of fallen enemies dissolving away instead of cluttering the environment.

But there's another aspect of persistence that complicates play, and that is persistence can lead to a failed game state. If you can make a change to the environment, and it stays that way, you can end up in a situation where you can no longer finish the game, because some persistent mechanism prevents you from doing so. Imagine filling a room with the dead bodies of your enemies, so that you could no longer walk through it to get to your destination. Or the hundreds of in-game puzzles you've played, where if a puzzle piece is lost or destroyed, it no longer magically reappears at it's starting location.

Respawning enemies usually exist not to continue to make your game harder and unrealistic, but because the rewards that those enemies drop allow you to refresh and regenerate your in game supplies so that you can continue to play - or in the worst examples, so you can increase your power through grinding to make any encounter trivial.

Detecting a failed game state can often be easy - and usually is rewarded with a game over screen, forcing you to start from before the failure. But not every failed game state is so trivially detectable. In fact, I'd suggest through a possibly flawed conflation of two ideas, that detecting failed game states is as complex as the Halting Problem, and therefore impossible in the general case. And the most frustrating thing would be for the player to fail to recognise the problem either, and continue playing from a situation where it is impossible for them to win.

So how does this idea of persistence translate to Unangband?

Well, with many roguelikes, each new dungeon level is a tabula rasa, a blank slate which the errors of the past can safely be erased. Angband is a canonical example of these: the only things to persist between dungeon levels are what you can carry in your inventory, the state you are in, and what the shops and your home holds. This works well for two equally important reasons: with procedural content generation, the game has an infinite amount of content, and so it is easier to throw old content away rather than keep it. And secondly, with procedural content generation it is easy to end up in an unbalanced or impossible game situation, so that provided eascape from the level is possible, the situation can be harmlessly wiped away.

But this lack of persistence breaks the suspension of disbelief, and encourages various types of game breaking behaviour: the worst of which is called stair scumming. With stair scumming, a player stays on the set of entry stairs to the level, climbing and descending them. Since each level is generated anew, it becomes possible to explore a large possibility space, looking for exploitable edge cases such as powerful rewards on the ground nearby, or powerful but vulnerable monsters that can be easily defeated.

It is possible to ensure disconnected stairs between levels to prevent this, so that when you arrive on a new level, you have to explore to find a return set of stairs, instead of them being generated under you. The drawback is that the same exploits that allow easy situations to be take advantage of, allows very dangerous situations to be readily escaped, should an unfortunate cast of the die, or whispered invocation of the RNG, fall the wrong way.

The solution, ultimately, is semi-persistent levels. These were implemented originally in Hengband. Semi-persistent levels are a compromise between the resets and wipes that non-persistence provide, with the stair-scumming prevention of persistent levels. With semi-persistent levels, all levels you visit persist, but are only accessible through the stairs you travelled to them from. With any other stairwell, up or down, you get a new level generated instead.

This ensures the dungeon is still infinite, because there are multiple sets of stairs exiting every level, but that you can visit any previous level by going back up the set of stairs you came down (or vice versa). You can't stair scum, because you just go back to the previous level you visited. But you aren't restricted in explorable dungeon scope, and the resource poor or badly laid out dungeon levels that the procedural content generation throws your way.

You can visualize a semi-persistent dungeon with your current level as the root node, and a branching tree of levels spreading away from it, with infinite leaves.

In part nine, I approach the end game.

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

19:16

5

comments

![]()

Labels: articles, procedural generation, unangband

Friday, 11 April 2008

These aren't the games you're playing for

It's always worth being reminded that the game you think you're playing (or designing for that matter), isn't the game you are actually playing. And it certainly isn't the game that the people at the top level are playing.

What do I mean by that? A canonical example is chess. There's two levels to learning chess: the rules of the game, and the consequences of those rules. The first takes maybe five minutes to master, the second takes a life time.

With that in mind, have a read of the following thread on Google about the strategy of playing Angband, written in a somewhat clipped style. I'll quote some of Eddie Grove's initial suggestions to discuss further:

To Win: kill Sauron and Morgoth.

need enough speed they are unlikey to kill you with double move.

need lots of hp and lots of healing, amount of healing depends

on hp and offense. Basically, game is about reaching 18/200 CON

and getting speed+20.

[...]

Every additional turn played lowers your chances of winning.

Learn wrong lessons before 2000'. Qualitative change in game.

Time spent before 2000' tends to reinforce bad habits.

Tedium and/or attention might be treated as resources.

Game is about multiplying bonuses and increasing stats.

Offense with avoidance is more important than defense.

Try to ignore monsters with no drops, but must kill

breeders, try to kill fast monsters rather than leave behind.

Free loot on the floor, try to keep as high as possible ratio of free loot vs

monsters killed, so no search mode and try to rest less for less monster regen.

Early game is all about selling. Do not test wands, want money

for each charge. Always id them. Only ones to keep are -lightbeam

and -trapdest and -stone2mud and -telOther. Otherwise, better to

sell for money for enchant scrolls for longbow.

Experience is unimportant. Comes automatically with survival.

Don't kill for exp unless you can do so quickly without using

consumables and not taking enough damage/mana that you would

consider resting. Exception if you will immediately gain a level.

than to spend two hours clearing an orc pit.

Now if you've played Angband but never got very far, the above information is vital. But at the same time, nothing in the game conveys this to you. In fact, much of the user interface of the game is counter intuitive in this sense. The experience counter and the reward of gaining levels implies that experience is important. The game reinforces bad habits, by allowing you to scum for items and gold forever, without reinforcing the good habits that Eddie highlights.

Angband is apart from other roguelikes, that it is much more about strategy and tactics than learning the game environment. In Nethack, a well-written spoiler could potentially help you win the game the first time you play. But in Angband, it is as much about recognising when you are in trouble, as having perfect information about the underlying rules. This comes directly from the hit point mechanic. If you have 600 hit points, 599 damage in a turn is inconsequential (providing you have a 100% reliable escape mechanism), 601 ends the game.

The other recommendations that Eddie makes flow from this, and his preference for winning the game in a timely fashion (also knowing as diving) as opposed to playing it forever (which is equally possible, and sure to be an issue as games take on more procedural content generation techniques).

But looking at the above list, my first instinct is want to change parts of the game to address these problems, because much of the flavour of the game is lost. But it's not fair to call these recommendations problems: they are consequences, just like the consequences of the rules of chess. And as a game designer, you can't change consequences, you can only change the rules that lead to them. And there is only a loose linkage between the two.

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

10:41

0

comments

![]()

Labels: angband, articles, game-design

Tuesday, 8 April 2008

Unangband Edit Files - Part Two (Customising)

(You'll probably want to start with part one of this series)

The edit files in Angband are a gateway drug: they exist to allow players to modify the game without requiring an understanding of coding or compilation. This is the reason there are so many variants of Angband – it is very easy for a player to modify one or more entries in an edit file to customise the game to their liking, and then progressively change the game so that it becomes a full variant. Outside the Angband community, these would be called mods or total conversions.

An understanding of the ability to read code is highly recommended if you wish to customise the existing edit files. This is for several reasons:

• The edit files themselves are incompletely documented. This file is an attempt to rectify part of that issue.

• Unangband is a work-in-progress and constantly evolving. This means that the SVN repository is the best place to get a view of the developer intentions, and the released source code for the version you are playing the best reference for specific implementation of the edit files.

• Documentation can at only at best discuss the code at a high level. For an exact understanding of how the edit files interact and features of these files, the source code and generated executables are your primary reference.

Luckily the Angband code base is well documented, a tradition that Unangband attempts to continue, although has done so in fits and starts. A later article in this series will provide a guide to reading the source code in conjunction with the edit files.

Customising the edit files is ‘simply’ a matter of making a change to the .txt file, saving it and restarting Angband. This will automatically update the corresponding .raw file as a part of the game start up. Various checks are made to ensure that the changes parse correctly, but not a lot of data bounds checking is enabled, so it is relatively easy to crash the Unangband executable, by putting invalid entries in the edit files.

If you wish to add entries to the end of a particular edit file, you’ll need to edit limits.txt. This file covers the initialisation of a number of maximum entries in each of the other edit files, as well as upper bounds for dynamically allocated memory for holding the text and descriptions for the majority of these files, and a few other values (e.g. the maximum numbers of monsters and objects on a dungeon level).

You should familiarise yourself with the game-play first, and then reading the edit files, before you make any changes. This will give you a good feeling for how changing the edit files makes corresponding changes in game. A common first attempt may be to make easy monsters have powerful or valuable drops, by adding various DROP_ flags to the monster type. Equally, monster vital statistics can be changed, allowing you to achieve impressive speed runs.

You’ll quickly learn (unless you are of a certain frame of mind), that changing the edit files to win the game quickly ruins the experience for you, and you should refrain from trying this, or even peeking at the information contained inside, to discover the surprises ahead. Unfortunately, this temptation is often too great – and a challenge that few open source games are likely to be able to overcome. But with the rise of sites like gamefaqs.com and programs like Glider, the same information sharing challenge is faced by commercial games as well. Luckily, the procedural generation, randomness and other roguelike features such as perma death ensure that Unangband remains a challenge, even with complete knowledge of the game rules.

The edit files are not as expressive as a full scripting language and you’ll find that there are a number of cases where various values in the edit file have hard-coded dependencies in the game code, or interact in unexpected ways. Unangband has tried to reduce the number of instances where this happens in the ‘core’ Angband edit files, but at the same time feature creep has meant that overall it is probably just as bad, if not worse than Angband itself. This series of articles attempts to address this.

(Stay tuned for part three).

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

10:59

2

comments

![]()

Labels: angband, articles, data driven design, unangband

Monday, 7 April 2008

Procedurally Generated Terrain Pictures

I've mentioned Infinity: The Quest for Earth previously, but a recent game development blog post features new screen shots of the terrain engine. Please remember that while the developer lists his nitpicks, and the screens themselves are impressive, the real power is that these are generated in real time in a continous and completely explorable universe.

I've mentioned Infinity: The Quest for Earth previously, but a recent game development blog post features new screen shots of the terrain engine. Please remember that while the developer lists his nitpicks, and the screens themselves are impressive, the real power is that these are generated in real time in a continous and completely explorable universe.

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

22:04

0

comments

![]()

Labels: links, procedural generation

Friday, 4 April 2008

How classy am I?

As a blog writer, I feel a degree of responsibility about publishing stuff on my blog. There's a certain amount of 'free content' that floats around on the Internet that could be used to pad out the size and frequency of blog posts, and which a few other sites are not afraid to use.

I'm slightly more principled. If I'm regurgitating an interesting story second-hand, I'll try to minimise the size I post, avoid spending a large amount of exposition that you've seen elsewhere, and try to not make my own spin on things, which in the long term may end up putting me in a hypocritical position. The fact this blog is a schizophrenic mix of roguelike minutiae and more general articles and is just as self-serving bothers me not.

So when I see the third or fourth blog post extolling you to find out What Kind of Dungeons and Dragons Character Would You Be? and filling the space with the blog writer's survey results, I just link it, and move on.

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

20:57

3

comments

![]()

Wednesday, 2 April 2008

Venkman and the Perfect Storm

After soliciting your advice (and ignoring it), I was hoping to have something to show you in return by now. But I'm stumped, and reduced to making 'Ghostbusters for kids'-type bylines.

After soliciting your advice (and ignoring it), I was hoping to have something to show you in return by now. But I'm stumped, and reduced to making 'Ghostbusters for kids'-type bylines.

I've started developing in JavaScript, using Mozilla canvas to prototype. I was able to get output in about 15 minutes and have refined it somewhat. JavaScript makes sense for me, because my work currently has a JavaScript component. It has a C-like syntax for arithmetic, comparison and loop operations which is of enormous help in making the transition, and I was able to quickly 'object orient' the code, although I'm mostly going to use this as a substitute for C structures.

But this slightly off the wall decision has cost me in the 'long run'. I'm now at the point where I've developed enough code to get silent bugs and need a debugger to trace through and understand the probably trivial syntax or logic errors I've already introduced.

Unfortunately, the obvious, and probably only choice, Venkman has left me plain confused. I'm not even sure how to start single stepping through the code I've written. I guess I should read some kind of tutorial.

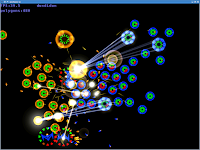

So instead, direct your gaze to Perfect Storm:

perfectstorm is a real time strategy game study written in common lisp using OpenGL for graphics display and cairo for texture generation. It is in active development with many of the basic features still unimplemented, but i decided the effort put into it justifies some public documentation.

Which is in the ballpark of what I'm hoping to achieve.

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

19:57

4

comments

![]()

Labels: links, programming

Praise for killing people

As an amateur developer, you're constantly on the look out for feedback. Which is why reading comments like this is so satisfying:

Unangband seems unique in that it's the one *band that whenever I die, I consistently think to myself, "now I know not to do that again." It seems that I rarely die to difficult or unique monsters; it's always due to some other (seemingly insignificant) reason. Maybe that's the thing that has kept me hooked on Un for so long over other variants - every time I die, I learn something new. It seems like a lot of the dangers from vanilla (eg. paralyzation, big poison breaths, etc.) aren't nearly so bad in Un (or maybe I've just never gotten deep enough yet). I like it.

Thanks Big Al.

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

18:54

2

comments

![]()

No torture. No exceptions.

It doesn't work. And you won the last big battle you fought by having better principles than your enemy. Why make a dumb mistake this time around?

(Thanks, PlayNoEvil)

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

17:19

1 comments

![]()

Labels: blog

Tuesday, 1 April 2008

Bug report: youtube no workee - fedora 9 not usable for wife

Even I have to appreciate this.

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

13:30

1 comments

![]()

2008: The Year of the Roguelike?

Verbal Spew is already declaring 2008 to be the Year of the Roguelike, based on the announcement that Chocobo's Mysterious Dungeon will be released later on this year for the Wii in the US.

I'd argue that every year is, but I'm happy for the suggestion...

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

11:37

3

comments

![]()

Labels: links, roguelikes

Programming language shootout: Time to bezier

I mentioned yesterday that I'm looking for a programming language with a short time from to go from zero experience with the language, to get vector graphics on screen. I suggested that it be multi-platform, and added various other requirements which are not as critical. And people came up with a number of excellent suggestions.

In the finest traditions of programming, I'm going to formally define my requirements, and ask for your help in a programming shoot out, to prove which language is best suited for the task.

My experience with development over the last 10 years, is that the ease of use of the end-to-end tool chain is critical for getting started with a new programming language. So the shootout is going to consist of the time to complete the following task:

Starting from a fresh install of the OS distribution of your choice, calculate the time to generate a downloadable executable capable of running on a freshly installed copy of Windows that shows a bezier curve on the screen. This must include time to locate and download the components of the toolchain used to do this using instructions available on the Internet.

If your language is interpreted, include the time required for an average individual to download and install the interpreter components on Windows. Ideally this should only consist of a single executable or installer which works using the pre-filled defaults. (penalize yourself 10 seconds for every keypress or mouse click that is required beyond this. You are allowed to count Ctrl-C for copy as one keypress)

For the advanced shoot out, which includes a self-hosting component:

You must start from 'step 1' which consists of - search Google for the keywords "[insert programming language name] [insert toolchain name] bezier curve" and proceed in steps deducible by an average high school graduate from a link on the first page of results, to generate the same downloadable executable.

You can include your own instructions written for the purpose of this shootout, provided you can get them onto the first page of results on Google.

In real world testing, I was able to get an advanced shoot out result in under 15 minutes. For bonus points, guess the language and toolchain.

For a 100% mark, in one hundred words or less you must apologise forexplain the fact your chosen language and platform takes longer than Logo on the BBC Micro.

Posted by

Andrew Doull

at

09:40

1 comments

![]()

Labels: articles, game-design, programming